Shirley Jackson is, among most Americans, only remembered for her deeply unsettling, controversial short story “The Lottery.” When it was first published in The New Yorker in 1948, it quickly became the most talked about work of fiction ever published in the magazine, with many writing in to complain or cancel their subscriptions.

This was in part because “The Lottery” is an amazing short story (the link above is to the full text, now available without paywall on The New Yorker’s website), but it was also in part because in the story, Jackson touched a sensitive American nerve. Americans, Jackson knew, are extremely prone to succumbing to a mob mentality, and can be totally thoughtless when it comes to their traditions.

For members of later generations, the story is still ubiquitous — it’s on most high school English class syllabi, and among the many stories I read as a high schooler, it is easily the most memorable. Until recently, this has been the extent of her notoriety outside horror circles.

Mercifully, the western world is reconsidering its literary canon, this time to include some writers who are not white men. And one of the quickest rising stars (though she died in 1965 at the age of 48) is Shirley Jackson.

A beginner's guide to reading horror

Spooky season is upon us! I’m a huge horror book buff, so it’s a good time to republish this article I did last year on the best horror. Original article (with more pictures) is here. The horror genre of writing is viewed by most "serious" critics as pulp or trash. This is bullshit. Serious critics are the worst, and they ruin everything that's fun -- ho…

The Haunting of Hill House

Her most famous novel is The Haunting of Hill House, which for my money, has the best opening paragraph of any horror novel:

“No live organism can continue for long to exist sanely under conditions of absolute reality; even larks and katydids are supposed, by some, to dream. Hill House, not sane, stood by itself against the hills, holding darkness within; it had stood so for eighty years and might stand for eighty more. Within, walls continued upright, bricks met neatly, floors were firm, and doors were sensibly shut; silence lay steadily against the wood and stone of Hill House, and whatever walked there, walked alone.”

This is a common theme in horror: that it might not necessarily be the supernatural that makes a place haunted, but instead its architecture. Horror icon (and virulent racist) H.P. Lovecraft loved to give alien buildings eeriness by referring to the fact that they were built with “non-Euclidean geometry,” and as such were beyond our mind’s ability to fully comprehend.

As I’ve mentioned maybe a dozen times in this newsletter, this jibes well with Alan Moore’s understanding of how places can drive us mad, because places we perceive as “rat traps” will make us feel like rats.

Jackson’s Hill House has successfully been adapted a number of times, but the Netflix miniseries (which did not stick close to the source material) was one of the spookiest things I’ve seen in years.

Dark Tales

As my first spooky book of spooky season, I’ve been reading Jackson’s short story collection Dark Tales. Horror as a literary genre is especially well-suited to short fiction. This is because the true greats in the horror genre understand that what’s most scary is the stuff that’s left up to our imaginations, and short stories as a form by necessity give you a lot fewer details and let you fill them in yourself.

If you are looking for one story from this collection to seek out, it’s “The Story We Used to Tell,” which is so eerie it sent a literal chill down my spine. It is also a very obvious predecessor to my favorite book of the year, Our Share of Night by Mariana Enriquez.

Book Rex: Our Share of Night

Juan is a medium. He can see ghosts and he can summon an eldritch entity known only as “the Darkness” from other dimensions to ours. Because of this ability, Juan has been forced into becoming the unwilling servant of an occult coven of brutal, wealthy dark art practitioners who collude with the right-wing Argentine military junta of the late 1970’s to …

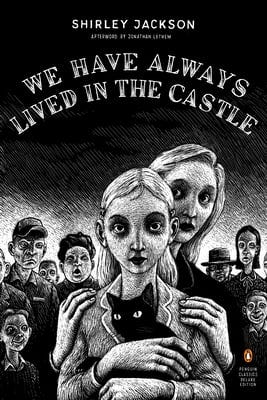

We Have Always Lived in the Castle

Jackson’s final work was We Have Always Lived in the Castle, about two sisters and a sick uncle who live in a mansion on the outskirts of town. The family is ostracized because, six years earlier, the older sister was accused of murdering the rest of the family. She was acquitted, but the question of who poisoned the family lingers, and only the younger sister has any contact with the outside world.

We Have Always Lived in the Castle is a dark look at what domestic life can feel like (Jackson herself raised her four children and supported the family with her writing while her husband had affairs with his students at the local college), and like “The Lottery” deals with the suffocating dread of living in small town America.

Shirley Jackson is not the scariest horror writer in American history, but she is among the best — any anxiety you’ve felt about this country and its culture is reflected in her work, and if you’re looking for a way to process those fears in a frightening time, you could do a lot worse than picking up literally any book she has written.