Hope vs. Optimism

What's the difference between hope and optimism, and why is hope infinitely preferable?

Nearly every time I’ve told someone they are a pessimist, they’ve replied with something along the lines of “I’m not a pessimist, I’m a realist.”

I will admit — this is a superb response. It is not correct, but it is condescending and infuriating, and it makes it very difficult to continue the conversation, which is presumably the point of the response.

The idea is that reality is bleak, and that anyone who doesn’t have a jaded, cynical view of the world must be a naive, delusional fool. And there’s a fair point hidden in there: optimism does suck. It frequently is naive and delusional, and optimists, in their expectation that everything will turn out fine, often are complacent and won’t take the appropriate action to fix a problem.

The issue is that pessimism also sucks, and can also cripple people into not acting. When what we need right now is an entire globe’s worth of people taking intentional actions to improve our collective future, the last thing we need is a pandemic of pessimism and despair, which is apparently what we’ve got.

To be clear — depression is a mental health issue, and it requires treatment and support, and no one should feel ashamed for being depressed. To a depressed brain, pessimism is less an intentional choice and more an involuntary reflex. To jolt oneself out of it requires therapy, exercise, social support, the ability to de-stress, and sometimes medication. It would also be helpful if global capitalism and its despair-inducing machinery finally collapsed.

But before that can happen, we need to envision a better future, and neither pessimism nor optimism alone will get us there. This is because optimism that ignores reality is pointless, and pessimism that ignores possibility is pointless.

What we need instead is hope.

Hope in the Dark

If you wish to truly, deeply understand the concept of hope, the book you need to read is Rebecca Solnit’s Hope in the Dark.

In it, the most succinct description of “hope” as a concept is given by the Czech dissident Vaclav Havel, which I’ve quoted on this newsletter before. Havel spent much of the 70s and 80s in jail as a political prisoner, and was in jail as late as 1986. When the communist state collapsed in 1989, he was elected President of the newly formed democracy of Czechoslovakia. On hope, he said:

“The kind of hope I often think about (especially in situations that are particularly hopeless, such as prison) I understand above all as a state of mind, not a state of the world. Either we have hope within us or we don’t; it is a dimension of the soul; it’s not essentially dependent on some particular observation of the world or estimate of the situation. Hope is not a prognostication. It is an orientation of the spirit, an orientation of the heart; it transcends the world that is immediately experienced, and is anchored somewhere beyond its horizons. Hope, in this deep and powerful sense, is not the same as joy that things are going well, or willingness to invest in enterprises that are obviously headed for early success, but, rather, an ability to work for something because it is good, not just because it stands a chance to succeed.”

It is this distinction that is most important for our purposes in differentiating between hope and optimism: optimism expects things to turn out well, whereas hope is a commitment to make things turn out well. Put another way, optimism sees the glass half full, hope is deciding to pick up the glass and put more water in it.

As practical guides to building a more hopeful mindset, I’d recommend a few books. I mentioned two of them in last week’s podcast on coping with chaos.

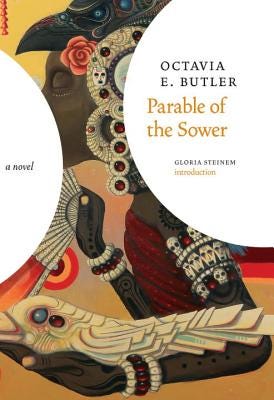

Parable of the Sower

Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower is an eerie, disturbing book about a dystopian future that is alarmingly similar to our present: it’s set in an L.A. with runaway climate change and a far-right President who ran on a platform of “Make America Great Again.”

The protagonist of the book, Lauren, is an 18-year-old black woman who has the ability to literally feel other people’s pain. She’s also a philosopher of sorts, and behind her Reverend father’s back, she designs her own religion, which she calls Earthseed. The core tenet of Earthseed is simple:

All that you touch

You Change.

All that you Change

Changes you.

The only lasting truth

is Change.

God

is Change.”

The book is intense, but it’s worth reading specifically for the philosophy, which is basically a how-to guide for dealing with chaos and upheaval.

Emergent Strategy

Activist and organizer adrienne maree brown is obsessed with Butler’s books, and off of the philosophy of Earthseed (and Butler’s other writings), she developed something called “Emergent Strategy” as a way of thinking and acting in the chaos that still manages to move us towards a better world.

brown is particularly talented in articulating the ways in which we can, as Butler would put it, “shape change.” This shaping change doesn’t have to mean you go out and become an activist — it could be something as simple as reordering the way you look at yourself and your personal relationships. This, brown points out, is its own type of activism, because you must change yourself if you wish to change the world.

The Dispossessed

Finally, I have to suggest Ursula LeGuin’s The Dispossessed. It’s often cited as one of the primary examples of anarchist utopia in fiction. It tells the story of a scientist who lives in an anarchist society, but nonetheless finds himself stifled by his comrades dogmatic take on their philosophy.

He moves to a U.S. style democracy, and finds that he doesn’t fit in particularly well there, either, but he is nonetheless able to advance his scientific work and his work as a teacher. If you don’t get a chance to read this book, it is worth knowing at the very least this one quote from it:

You cannot buy the revolution. You cannot make the revolution. You can only be the revolution. It is in your spirit, or it is nowhere.