How a different understanding of time can help you cope

Albert Einstein, Alan Moore, and the "Grand Illusion" of Time

I am not often jealous of the religious, but I do wish I could believe that bad people like Donald Trump or Vladimir Putin would burn in hell for all eternity. From a purely moral and philosophical standpoint, I find the concept of heaven and hell to be repugnant, but, but, it is a neat little trick for bypassing fury at all of the injustices of the world. Someone’s a dick? Fine. They’ll get theirs. Not your problem anymore.

I have no such luxury. I think Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin will probably end their days with immense wealth and power, which they will use to shield themselves from the consequences of their actions. And then when they’re dead, they’ll just decay in the earth, while we deal with the fallout.

I am also jealous of the religious who can bring themselves to believe that whatever happens to them is all “part of God’s plan.” Again — from a philosophical standpoint, I find this to be nonsense, and from a moral standpoint, God’s got a few things to answer for. But! This would take all of my anxiety about the future off of my plate. It would be out of my hands and in God’s.

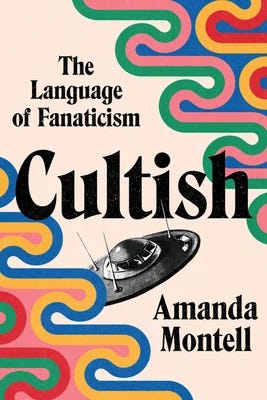

Religion excels at providing all of these little workarounds — they are what linguists who study religion and cults call “thought-terminating cliches,” and they are enormously useful for reducing anxiety.

In my post-religious journey, one of the major problems has been having nothing particularly certain to grab onto. Because I have trouble committing to beliefs that may be bullshit, but which require faith to work, I’ve had to deal with a lot of anxiety, and I’ve now moved through a lot of different philosophies that have eventually collapsed under the weight of scrutiny or experience.

The closest thing I’ve found to comfort is a view of time that I first encountered in sci-fi books like Slaughterhouse-Five by Kurt Vonnegut. It’s called Eternalism, and it is one of several possible views of time arising from Einstein’s Theory of Relativity.

The Block Universe

Einstein’s main realization with the theory of relativity was that time existed much in the same way space does — hence his referring to our objective reality as “spacetime.” In Kurt Vonnegut’s classic sci-fi war novel, Slaughterhouse-Five, he explains this with an alien race that can see all moments in time at once, viewing time, as he puts it “as you might see a range of the Rocky Mountains.”

(I talked more about the fictional ideas of this and its implications for things like trauma and forgiveness in my “Against Forgiveness” article below.)

Against Forgiveness

Listen now (15 min) | Hey everyone! I am dragging a bit! Pandemic mental health stuff caught up to me, so instead of original content today, I am providing an audio version of my favorite ever column, which was originally titled “Against Forgiveness” and was then changed to “Forgiveness and Time” on Better Strangers.

The idea was expanded on by comics writer Alan Moore, whose character Dr. Manhattan sees time much as Vonnegut’s aliens do. For him, with his superhuman powers, all events are happening simultaneously, and this puts him at a distance from human experience.

Moore doubled down on the idea with his epic novel Jerusalem, which has the idea of Eternalism at its core. He suggests that we can view time much in the way we view a book: we read it linearly, moving left to right, down the page, turning the page, etc. But when we turn the page, the words we read don’t cease to exist. They’re still there, we’re just only paying attention to the word we’re on. Moore suggests that what we do when we finish the book is we just go right back and read it again.

In this sense, every terrible moment of our lives is eternal — a literal hell. Every wonderful moment of our lives is also eternal — a literal heaven.

This concept of living destroys the notion of free will, of course — if we live in a block universe then our future is already written — but it also gives us a moral reason to truly live in the moment and enjoy our lives as much as possible, because our joy and our misery are eternal.

What’s most appealing to me about this idea, though, is that it takes the pressure off of us to have a long, full life. If we have a short life — say it’s cut short by a climate catastrophe, a nuclear apocalypse, or — that most banal of American deaths — by a mass shooting, then what matters is not so much the time we didn’t get, but the time we did. A short life, in this context, can still be a full one. Who cares if you get 36 years of eternity instead of 100? It’s still eternity. And the incentive becomes to have a life that’s as rich and fulfilling as possible, no matter what the length or the ultimate outcome of our actions. We are free from the tyranny of our legacy. Better yet, we are, in a sense, free of the loss of our loved ones. We still have to grieve them when we die, but that moment we sat on their knee as a toddler is real and always will be, somewhere back in the ether.

Thought-terminating cliches

It’s worth noting that, while many physicists and philosophers believe in Eternalism as a viable understanding of spacetime, many others don’t. For them, the only moment that’s real is the present, and this view is called “Presentism.” My guess is you could still get a pretty interesting and life-affirming philosophy out of that as well, but it’s captured the imagination of fewer of the sci-fi writers I like, so I’ll go with Eternalism for now. Also, the KLF already wrote a song about time being eternal, so I have my first hymn, I guess?

Eternalism as a philosophy is on more solid ground than “God has a plan,” for sure, but it is a philosophy based on ever-shifting science. Should physicists ever develop their “Theory of Everything,” which unites the seemingly contradictory worlds of relativity and quantum mechanics, there’s a good chance it would totally upend this view of the universe.

But until then, it serves for me as a semi-scientific philosophy that allows me that wonderful thing that is usually only available to the religious: the thought-terminating cliche, the article of faith.

Because now, at 36, I’ve realized that there are times in which I just need, for the sake of my mental health, to stop thinking about things and letting them go. Religious thought-terminating cliches like, “Let go, Let God,” sound creepy and insidious to my ears, and they can certainly be abused as a way to keep your followers ignorant and unquestioning. But the fact is, sometimes unanswerable questions just need to be let go of, at least for a time, until you can come back to them with fresher eyes.

That’s the paradox of being a human — we require philosophies to function, but all of our philosophies are embarrassingly incomplete descriptions of reality. We have to, by necessity, put our faith in things that are possibly ridiculous, even wrong.

It is better that we think of our philosophies and ideologies as tools, items that are to be picked up to help us through a certain moment, and put down when that moment is over. Humans may require faith to function properly, but there’s nothing absurd or irrational in believing that the hammer will help you pound in the nail.

Also, OMG I 100% forgot about that song, lol.

Really good one, Matt. Thanks!