For as long as I can remember, I’ve been obsessed with dystopias. I watched every zombie movie I could, I read every book about every bleak wasteland, I obsessed over Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, I got into impassioned debates about The Dawn of the Dead slow zombies vs. 28 Days Later fast zombies, and as a game with my friends, I’d strategize about what I’d do during a zombie apocalypse.

Around the time of my daughter’s birth, though, I recognized that I didn’t have any sense of what a positive future could look like. And that was a bleak thing to confront during dark nights staying up with a crying infant.

The reason I was so hopeless about the future was simple — I’d never engaged with utopias. Only dystopias. And it was not just me. As the British writer John Higgs put it in an interview with The Ransom Note:

I think the problem is that at some point in the 1980s we gave up on the future. Before then there were all these positive futures imagined in things like Star Trek. It seems to me that the last ditch attempt to say something positive about the future was in 1989 in Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure, when they say ‘The future will be great — it’s a bit like now, but with really great waterslides’. That was the best they could do. Ever since then the future has been shown as environmental apocalypse, zombie films, all of these things. And to create the future, first you have to imagine it, so this is a very worrying thing.

In Higgs’ other writing, he’s discussed how the science-fiction of the 50s and 60s, while often flawed, was at least aspirational. We were imagining ourselves among the stars, learning more about the universe and our place in it, engaging with alien life, pushing the bounds of human consciousness, and so on.

Now, an enormous chunk of our YA fiction — the stuff that we’re feeding our kids on a massive scale — is Hunger Games and its rip-offs.

We have simply lost the ability to imagine a better future.

The purpose of -topias

In 1891, Oscar Wilde wrote an essay called “The Soul of Man Under Socialism,” in which he argued that capitalism forced us to live lives that weren’t truly our own, and that if we wanted to build a better world, we should focus less on giving to charity and more on simply changing our system. The essay, which was heavily influenced by Wilde’s readings of the revolutionary anarchist Pyotr Kropotkin, contains one of his most famous quotes:

Is this Utopian? A map of the world that does not include Utopia is not worth even glancing at, for it leaves out the one country at which Humanity is always landing. And when Humanity lands there, it looks out, and, seeing a better country, sets sail. Progress is the realisation of Utopias.

This is not a particularly modern stance. To be seen as optimistic about something in 2023 is synonymous to being seen as naive. It is impossibly cringe to hope that things could get better.

We’re far more comfortable with dystopias. And in their defense, dystopias when done right are incredibly useful tools. George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four has enormously important things to say about how power wields truth and language. Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World eerily predicted how capitalism would exploit entertainment and spectacle to keep people distracted and docile.

For me, growing up in the 90s and 00s in conservative Cincinnati, a big part of the appeal of dystopias was that they seemed to acknowledge a nagging feeling that I had, that actually we weren’t in the best country in the world, that this wasn’t the end of history, that things did actually kind of suck.

But that idea is no longer subversive. The conservatives that I grew up with also now think that the country is terrible, they just blame minorities and sinister liberal cabals instead of the capitalist class and the people who are actually in power.

What’s more, we’re now far more aware of just how bad things could get, because we lived through Donald Trump. We’ve watched our government totally fail to protect us from a global public health crisis, and we’ve watched our collective mental health decline enormously in the wake of COVID-era social isolation and our growing addictions to depressants like alcohol and smartphones.

What’s more, many of the more recent dystopias have sacrificed the social message that they’re supposed to serve in the name of character-based drama. I can’t particularly distinguish a strong social message, for example, in The Hunger Games, as it seems that we, the audience, are no different from the rich in our leering at these children killing each other book after book. And as great as The Last of Us has been, it seems to have a pretty dim, bleak view of humanity, one that is contrary to our best evidence about how humans really respond to calamities.

This immersion in dystopian hellscapes has an effect on our mental health. When we picture our children’s futures, we are only picturing civil wars, rising oceans, irradiated wastelands. It is only adding to our mental health crisis. We need to think of something better.

We need to imagine beautiful futures

The best thing I’ve discovered in my brief time on BookTok, the book corner of TikTok, is the idea of hopepunk literature. Hopepunk is not really a genre — it is more of a literary stance against a more popular classification known as grimdark. The quintessential grimdark series is Game of Thrones. The quintessential hopepunk series is The Lord of the Rings.

While the two series often feel thematically similar, you can easily spot the difference in their tones: Lord of the Rings depicts the good life as one of singing songs, drinking ale, and stealing carrots from Farmer Maggots crop. Game of Thrones is all murder and rape and mutilation.

What distinguishes the two is not the presence of dark, terrible deeds, it’s their attitude towards them. In GoT, they are inevitable, part of the human spirit, and in LotR, they are perversions, a break from the natural order, something that is overcome with kindness, bravery, and teamwork.

These are the types of stories that frankly need more telling — stories which do not take brutality and annihilation as a given, which take hope seriously.

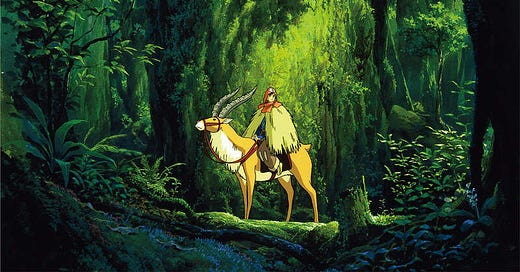

A second genre that we need to pay more attention to, if we want to have any chance at a future, is solarpunk1. Solarpunk is a genre that imagines a sustainable future, in which people figure out a way to live in harmony with nature, rather than by constantly exploiting it. The two highest-profile practitioners of this genre are probably Ursula K. LeGuin, with works like The Dispossessed and Always Coming Home, and the animator Hayao Miyazaki, who made sustainability and communion with nature the core theme of his masterworks Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind, Princess Mononoke, and Castle in the Sky.

These works already exist, but they are not absorbing enough of our attention if we truly want to build something better. It is all well and good to recognize that which is wrong with the world, but unless we also have a positive vision for the future, nothing will change. You can’t walk down a road you can’t even see.

I know, I know: everything has to be a “punk” apparently.