In (slightly belated) honor of St. Patrick’s Day, I wanted to offer an Irish-themed Book Rex. My ancestry is that of an American mutt — if you looked at my DNA breakdown, you’d notice that my ancestors seemed particularly indiscriminate about what sort of white person they coupled with, and you’d maybe mutter to yourself, “well, at least they were indiscriminate about something.”

But the strongest cultural connection my family had was to its Irish roots, which we celebrated by doing extremely American things. As I’ve deconstructed my identity as a white American, with all of the horrific baggage that involves unpacking, I’ve found myself casting about for an identity to replace it with, and the Irish bit has been the most accessible, with its English-language cultural offerings, its holidays, its music, and the fact that, unlike my English and American ancestry, it is the history of a colonized people rather than a colonizing people.

This is — and I know how bad this sounds — something of a relief for a cis, straight, white American man, who otherwise has to grapple with an ancestral legacy of brutality, cruelty, exploitation, and oppression. It’s nice, for once, to be able to identify as the underdog. Because as a leftist, I want to fight on the side of the oppressed, but as a cis, straight, white American man… well. I usually know who’s being fought.

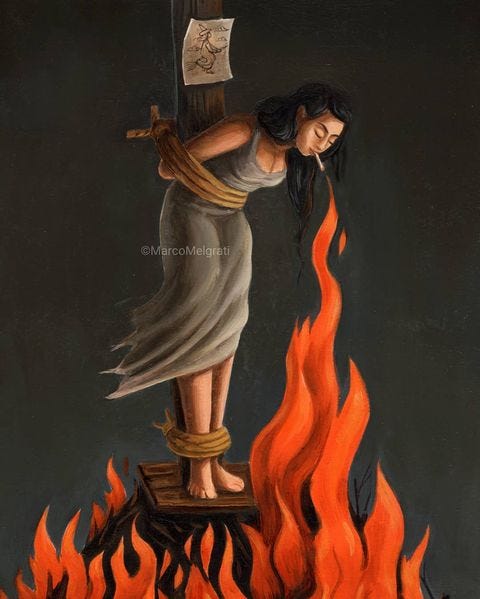

My wife has a print of this painting hanging over her side of the bed:

It’s a lovely clarifying picture, particularly for a woman who works in politics, to look at every morning when she wakes up. It is hard not to be jealous. Nothing is quite as clear to me — so much of my identity growing up was rooted in toxic masculinity, right-wing politics, homophobia, and coded racism1, and so much of any alternative identity has been so thoroughly severed from its roots, that I have to live vicariously through other people’s struggles, and try to imagine what I would be like in their place.

Which is why I read Say Nothing. But the book did not oblige — it had no easy answers for me.

Say Nothing by Patrick Radden Keefe

In 1972, Jean McConville, a widowed mother of ten, was "disappeared" from her flat in Belfast by masked men and women, never to be seen again. Hers was one of hundreds of deaths in "The Troubles," the struggle between the Irish Republicans and the pro-British Unionists in Northern Ireland, but her death was unique in that it exposed a major tension in a country trying to mend itself: sometimes peace and justice are conflicting forces.

Patrick Radden Keefe tells the story of McConville's disappearance mostly through the eyes of the woman responsible for it — Dolours Price. Price was raised in a gung-ho IRA family, and was thoroughly radicalized in the fight for Irish reunification. The IRA, while nominally aligned with Catholicism, was in this era a politically socialist organization, and viewed itself through a revolutionary lens.

Price was the ringleader for a series of bombings in London, and also participated in a number of hits and assassinations. She was caught by the English and was thrown into prison, where she began a hunger strike in order to be moved to a prison in Northern Ireland. The English shoved a tube down her throat and force-fed her. She developed a lifelong eating disorder after that.

When she was released, Price began distancing herself from the IRA, who had begun seeking a peace agreement. Sinn Fein, the political party that was strongly tied to the IRA during the Troubles, was led by a man named Gerry Adams, who for years insisted that he had never been a member of the IRA, and was a major actor in the eventual Good Friday Peace Agreement. But Price later openly testified that her leader when she was in the IRA was Adams himself.

Worse, Price said Adams was the man who ordered Jean McConville’s death, on the intelligence that she was passing information to the British.

This complicated the peace process, because to go after Adams was to risk antagonizing and alienating members of Sinn Fein who had up until then been committed to the peace process.

This is just a spectacularly written book, it reads like a thriller and is an astounding work of journalism. It is 100% worth the read.

Ireland and me

I have been to Ireland: not for a long stretch, maybe three days. But that’s long enough to know that most of the things I associate with being Irish in America — drinks that are astoundingly called “Irish Car Bombs,” the Fourth of July-style parades, the absurdly kitschy shamrock paraphernalia — are not Irish at all.

The last family member that I know of who lived in Ireland came over to America in the late 1800s. Most of my Irish ancestors were escaping the Famine. I think, though, that I can trace a similar lineage of trauma and violence between myself and the likes of Dolours Price or Jean McConville. My experience is much more mundane: there are no freedom struggles in my near ancestral past. My, in fact, family largely cut themselves off from their ancestral past, instead opting to believe in their adopted country’s beautiful lie, the American Dream. Irish ancestry bubbled out once a year, on St. Patrick’s Day, when sad or silly Irish songs were sung, when melancholic feelings bubbled up over a few drinks.

After reading Say Nothing, I suspected that had I been a young man in Belfast at the time of the Troubles, I would’ve joined the IRA. The underdog identity, the socialist politics, the camaraderie — it all would’ve been too seductive for me.

I am glad that’s not how it panned out. Retired terrorists do not have an easy time of it: In her later life, Dolours Price struggled with her eating disorder, with alcoholism, and with prescription drug abuse. She died of an overdose at 62.

My family’s legacy, the Ireland they fled, is lost to me. My ancestors forgot well. But the symptoms of the Ireland they left linger on — the trauma, the mental health problems, the abuse, the alcoholism. It’s nice, getting to have that same inheritance without having to have done any of the terrorism.

Or maybe I’m just a masochistic white guy, so devoid of identity that he needs to fabricate it out of a perceived ancestral oppression. Maybe it’s pointless trying to ascribe political meaning to your trauma. Maybe you just have to feel it so your kids, at an even further remove than you, can feel it a little less.

Éirinn go Brách! Póg mo thóin! Watch kids, as your dad gets sad! This is your heritage!

Usually coded.