Fighting nihilism by watching Casablanca a million times

The classic film remains wildly relevant in an era when so many people are choosing despair and nihilism.

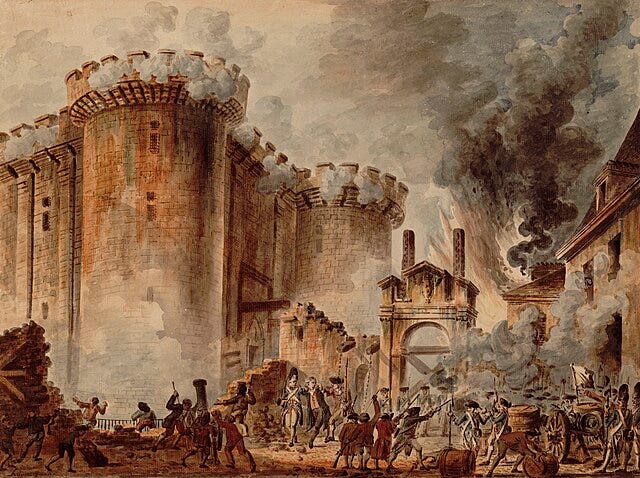

Friday is Bastille Day, which is the day during the French Revolution when the common people stormed the notorious Bastille, a fortress, armory, and holding place for political prisoners. It’s now celebrated as France’s Independence Day, which, for my money, is at least part of the reason the French get what they want from their government so much more than we do. Any nation that celebrates itself by commemorating the storming of the prisons is gonna be cooler than the one that celebrates rich guys signing an angry letter1.

It’s also my birthday! Each year on my birthday I hang a French flag at our house, pour myself a glass of scotch, and watch my favorite movie, Casablanca, with my wife, kids, and some friends. We do our best at singing La Marseillaise, but we absolutely butcher the French.

Casablanca has been a touchstone of hope for me for about two decades now, and if you’re struggling with nihilism in these dark times, it may be worth a watch.

There will be some spoilers here, but you’ve had 80 years to watch the movie, so you know, get off your ass. I’m genuinely not kidding, this synopsis is an atrocious substitute for a nearly perfect movie.

The temptation to believe in nothing

In his fantastic book Stranger Than We Can Imagine, the English writer

suggests that while the story is undoubtedly of its time, with its World War II themes and its low-key racism towards the character Sam2, what makes it timeless is that it is an effective argument against nihilism.The movie was written and shot in the early days of US involvement in WWII, when victory was far from certain. Much like today, it would’ve been an easy time to despair about the apparent collapse of the world, to simply give up on everything and focus on yourself.

That sentiment is embodied in Humphrey Bogart’s character, Rick Blaine, the jaded nightclub owner who publicly pronounces “I stick my neck out for nobody,” and makes money off of refugees who are desperately gambling in his casino to win their way out of the Vichy-controlled Casablanca.

Rick’s nihilism is tested when his former lover, Ilsa Lund (played by Ingrid Bergman) arrives in Casablanca on the arm of famed antifascist dissident Victor Laszlo. When Ilsa left Rick, it destroyed him and ended his idealistic streak, turning him inward and bitter. But with their arrival, Rick is suddenly put in a position where he can either help Laszlo escape, or throw him to the Nazi wolves — and possibly get his girl back in the process.

Now: there are a trillion reasons I love this movie. It is shot beautifully, it’s writing crackles, the performances are stellar, and the scene in which a room full of actual European refugees drown out the Nazi anthem with La Marseillaise makes me cry every single year3.

But Higgs is right — what really makes Casablanca timeless last is that it is an argument against selfishness, against nihilism, and for idealism and hope.

The choice between hope and despair

Rick’s ultimate choice is to stick out his neck — and with no apparent benefit to himself. He helps Laszlo flee Casablanca, puts Ilsa on the plane with her, and then with the Vichy Chief of Police who aided him, flees across the desert to a Free French garrison with a bounty on his head.

And that is what I love about Rick’s conquest of nihilism — it’s his choice to do so. As someone who struggled with nihilism for years, I can tell you the overwhelming urge is to believe that everything is meaningless, and that there’s no point to fighting for anything. I was waiting for the world to give me meaning, in a bolt from heaven, or in a sudden opportunity, or in a flash of insight.

But hope is not something the world gives you. It is a choice you make to commit yourself to something that you find meaningful and valuable. And often that means doing so in the face of overwhelming odds — say, the onslaught of the Nazi’s machine of mass murder and brutality, or the complete destruction of the biosphere at the hands of capitalism.

You don’t make this choice because it’s going to materially earn you anything. You make it because you feel it’s right, because it aligns with the very core of who you are in some way. That choice may put you in danger, but that doesn’t matter — you’ll know it’s better to fight for what’s right and lose than to have never fought at all.

For me, Casablanca is a yearly reminder that choosing hope is a beautiful thing to do, and while not all of the people who do so live to see the results, hope can topple impenetrable prisons and defeat unbeatable armies.

Fun fact: The actual key to the Bastille was given by the Marquis de Lafayette to President George Washington as a gift, and it sits at Mount Vernon today. I personally don’t feel that the key to a notorious prison is the liberative symbol that Washington may have thought of it as.

The actor who plays him, Dooley Wilson, still owns the movie though, and transcends the stereotypes the screenwriters saddled him with.

Madeleine Lebeau, the actress in the thumbnail to that video who is crying, was actually present at the Nazi invasion of Paris, and, like Rick in the movie, barely escaped to the United States. Her tears in that scene — and her iconic cry of “Vive le France!” at the end — are 100% real.

Happy early birthday! And this makes me think I should rewatch Casablanca…I don’t think I caught everything when I watched it as a freshman in college 😁