On my sudden mid-30s obsession with birds

What started as an early pandemic "Birdman of Alcatraz" bit has become an unusually large chunk of my personality.

When my son was born in February of 2020, we knew we would need to move to a new house soon, but we loved our apartment — it was a cozy second floor two-bedroom, it was where we’d spent the first two years of my daughter Sophie’s life, and we knew that in my wife's late pregnancy the stress wasn't worth the move. Instead, we nested, and focused on enjoying the last few months with Sophie where there was just three of us. We planned on getting a place with three bedrooms after the rough first months following my son’s birth. Until then, he'd sleep in a bassinet next to our couch, or, more likely, swaddled in the warm cloth carrier we draped around our torsos.

But a month into his life, COVID hit, and suddenly, we were without daycare. New Jersey was one of the earliest and hardest hit, so the closures were sweeping and widespread, and included the public parks. They still weren't sure, they explained, if the germs could linger on surfaces, and this made playground equipment dangerous.

When I mentioned on a local Facebook page that this made it hard for families with young kids and no yards, a neighbor told me to just take Sophie to a nearby road and sit her on a bench, so she could watch cars go by. I gently suggested that I was not positive she had ever physically sat down, and that attempting the experiment in busy traffic was not my idea of “blowing off steam.”

Instead of a yard, we had an empty lot next door, so the entirety of our time outside the apartment became the hour or so a day, rain or shine, when I would take my daughter into the empty lot, to give my napping wife and son a few moments of peace and quiet. Sophie would run around and splash in puddles while I picked rusty cans and nails out of the property and tossed them into the trash.

Once the lot was more or less cleared of debris, I began to get bored just standing in it, and I needed something to do. So I downloaded nature apps — iNaturalist, Merlin Bird ID, and Seek, which allowed me to use my phone’s camera to identify every plant and bird in the yard. The first plant I pointed it at happened to be poison ivy, which made it instantly useful. After moving Soph away from the plant, we went on scavenger hunts for weird bugs and mushrooms, and we began listening to bird calls to try and identify them. In doing so, we could hear the thrice-repeated patterns of mockingbird calls, and look up and catch them flying in their characteristic wavelike parabolic swoops.

The hobby grew to the point that I bought a window feeder, which I installed on our second story window, right in view of the couch so I could watch starlings and house sparrows fight over the seeds while my infant son napped on my chest. On days when we never left the apartment, it felt like my only connection to the wider natural world, like I was the Birdman of Alcatraz.

As I grew more proficient, I could tell which birds were outside the apartment without looking — if I was woken up at 3 AM by a truly thunderous cheerily! cheerily! cheer up! I could tell that it was a robin1, and if I heard an ugly, throaty screech, I could tell if it were a crow, a fish crow, or a blue jay.

After our initial, hellish, 14-day quarantine, we would spend our weekends in Point Pleasant with Steph's parents, who had a whole different set of birds living in the swamp along Beaver Dam Creek. One early morning, when Sophie woke up early, I sat on their deck chairs outside sipping coffee when the two-year-old said, "Papa, that's a mourning dove."

I reflexively began to correct her and then paused and heard the unmistakable, sad, coo-WOO-woo-woo-woo. It was a mourning dove.

I’d heard it lamented that today’s kids can recognize 100 corporate brands by the age of 3 but couldn’t name any local plants or birds. My kid, at least, knew dandelions and mourning doves.

Small ideas

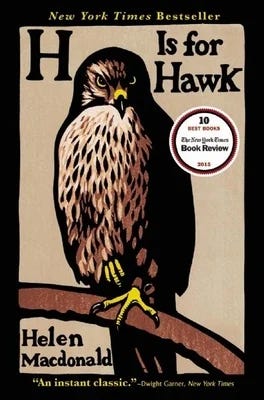

I recently read Helen Macdonald’s wonderful H is for Hawk. The book, if you haven’t read it, is about how, in the wake of her father’s sudden death, the author adopts and trains a wild goshawk named Mabel. There’s a bit in it where a misogynist acquaintance suggests that the reason she gets along so well with her hawk is that they are both women. She recognizes it as an astoundingly stupid comment, but in her research finds that this was a common theme among Victorian male falconers — rather than a hawk being difficult to train because it’s a wild animal, it must be difficult because it’s a hormonal woman.

While pondering this, she notices something — her goshawk, Mabel, is trying to play with her.

Her eyes are narrowed in bird-laughter. I am laughing too. I roll a magazine into a tube and peer at her through it as if it were a telescope. She ducks her head to look at me through the hole. She pushes her beak into it as far as it will go, biting the empty air inside. Putting my mouth to my side of my paper telescope I boom into it: ‘Hello, Mabel.’ She pulls her beak free. All the feathers on her forehead are raised. She shakes her tail rapidly from side to side and shivers with happiness.

An obscure shame grips me. I had a fixed idea of what a goshawk was, just as those Victorian falconers had, and it was not big enough to hold what goshawks are. No one had ever told me goshawks played. It was not in the books. I had not imagined it was possible. I wondered if it was because no one had ever played with them. The thought made me terribly sad.

The passage struck me because it’s been one of several of recent instances in which I’ve found myself relating to a bird.

This is because the 5 years I’ve spent as a parent have done strange things to me: I’d had a pretty good sense of who I was as a person in my earlier adult life, and I felt I had a solid grasp on how the world worked. I thought of myself as smart, I thought of myself as sarcastic and somewhat jaded, an atheist or an existentialist, depending on the day. I knew I listened primarily to rock, alternative, and blues music, I knew I read horror novels and long books written by old Russians, I read nonfiction on politics and philosophy. I knew I was good at debate, I knew I was more of a city guy than an outdoors guy, I knew I liked to travel and write. I had a ground to stand on.

And my kids stuck a shovel into that earth, pried it loose, and flipped it. I was suddenly a cryer. Sarcasm and debate were useless with toddlers, and I couldn’t read bleak books on climate change and existentialist philosophy and come home prepared to deal with a smiling baby. Suddenly I wasn’t smart — there were emotional skills I needed for children that I was not only bad at, I was completely stunted on.

Not only that, my tastes had suddenly changed — I was all of the sudden really connecting with metal, with synthpop bands like CHVRCHES, with niche genres like witch house, and, god help me, Sovietwave. And oh yeah! No big deal! Atheism wasn’t working anymore! I was all of the sudden slipping towards a weird version of neopagan spirituality, and was lighting ritual fires with my kids on the winter solstice while telling them stories about The Wild Hunt.

I’d had a fixed idea of who I was, and it was not big enough to hold what I am.

Beach walks

One of my shifts has been by necessity — I live close to both New York City and Philadelphia in a physical sense, but having two young kids means I rarely go there. So I just don’t really get the opportunity to be a city guy anymore. I do, however, live less than a mile from the beach. Which means that I can go there early in the morning, before the kids wake up, or after lunch for a stroll.

While I walk, I try to use the eBird app to keep track of the birds I’ve spotted. I convince myself this is for citizen science, but really, I just want to get to know my neighbors, because they made me feel better on a day I’d been feeling sad.

After a rough morning (followed by an intense therapy session) I’d gone to the beach in the rain, and had gotten cold and drenched. The shore was covered in birds — common loons, long-tailed ducks, great black-backed gulls — and at one point, I saw a flock of brants in a V-formation, their wing tips barely missing the waves.

It was one of those brief out of body experiences you have when you see something wild — the sudden realization that these are living creatures, and that even though they are literally in your neighborhood, they are having experiences that are completely outside your world of doomscrolling and daycare drop-offs and pots of coffee. Their lives are rain and sea spray and eating seaweed and moss and huddling together with their flock on the cold nights. What’s more — I felt like I could imagine myself as them.

When we left our COVID-era apartment, we moved to a house in a nearby town. I set up three birdfeeders in the yard so I can bring the wild animals a little closer to me. I now strategize about keeping local cats out of my yard and away from my birds (cats are invasive species, people, keep yours indoors), and I go on hikes through a nearby woods in the hopes I’ll see the local fox (whom I’ve named Kaiser Fuzzyface) darting away from me through the dead leaves.

After a lifetime of putting myself and my world into understandable boxes, it’s nice to have these constant reminders, not that I was wrong, necessarily, but that the boxes were never big enough to fit everything in them. There is still more to discover, even about myself.

If anyone’s wondering which birds get the worm — it’s robins.