One of my favorite bits in Hunter S. Thompson’s Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas is when he settles in his hotel room, his body absolutely chock-full of illegal chemicals, and tries to calm himself out of a frenzied panic1:

By this time the drink was beginning to cut the acid and my hallucinations were down to a tolerable level. The room service waiter had a vaguely reptilian cast to his features, but I was no longer seeing huge pterodactyls lumbering around the corridors in pools of fresh blood. The only problem now was a gigantic neon sign outside the window, blocking our view of the mountains -- millions of colored balls running around a very complicated track, strange symbols & filigree, giving off a loud hum....

"Look outside," I said.

"Why?"

"There's a big ... machine in the sky, ... some kind of electric snake ... coming straight at us."

"Shoot it," said my attorney.

"Not yet," I said. "I want to study its habits.”

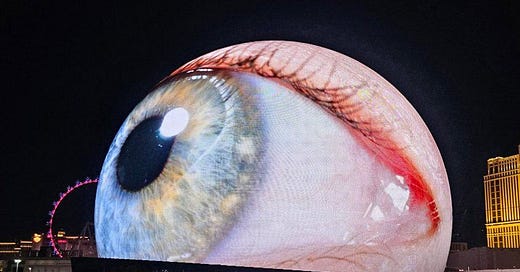

Thompson was an expert on both fear and loathing, and spent much of his life on a frenzied, paranoid, drug-addled bender that would’ve killed most rhinoceri. It is perhaps fortunate that he did not make it till 2023 — he would not have handled the rise of far-right politics particularly gracefully for one thing. For another, Las Vegas now has art installations that are pulling shit like this:

I love that moment in Fear and Loathing, though, because it’s one of those rare moments where Thompson breaks through the violent paranoia into a moment of lucidity, and instead of being crippled by fear, he becomes curious about what he’s experiencing.

The Death of the American Dream

I first read Fear and Loathing in one sitting while my mom drove me to the first week of my freshman year of college. It was a fortuitous time to read it, as it ended up defining the next decade of my life. I was coming out of a conservative Catholic upbringing and was beginning to suspect most of what I’d been told about the way the world worked was bullshit.

The next few years would prove me right: the economy would collapse in 2007, right before I graduated, and my generation would never recover. My degree in journalism — I’d decided to switch to this profession from film shortly after reading Fear and Loathing — became effectively useless the year I graduated, as newspapers across the country shuttered their doors. I completely abandoned (and later actively opposed) the Catholic faith of my childhood, and any sense I had of America as the “land of opportunity” fell apart as I went abroad and, quite simply, saw more opportunity in other places, including fucking Communist China.

Hunter Thompson, then, was the perfect author for me: the main theme of his work was “the death of the American Dream.” His most famous bit from Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas is the “Wave Speech,” in which he discusses the end of the hippie era in San Francisco:

There was madness in any direction, at any hour... You could strike sparks anywhere. There was a fantastic universal sense that whatever we were doing was right, that we were winning. . . .

And that, I think, was the handle—that sense of inevitable victory over the forces of Old and Evil. Not in any mean or military sense; we didn’t need that. Our energy would simply prevail. There was no point in fighting—on our side or theirs. We had all the momentum; we were riding the crest of a high and beautiful wave. . . .

So now, less than five years later, you can go up on a steep hill in Las Vegas and look West, and with the right kind of eyes you can almost see the high-water mark—that place where the wave finally broke and rolled back.

For millennials like myself, adulthood has been a series of breaking waves. The promise of the economy broke in 2007, the promise of a better political future broke in 2016 with the election of a literal fascist, the promise of a livable planet for our kids seems to be breaking now as we choke on the very air we breathe.

All of this despair is overwhelming, and it is no surprise that so many of us are struggling with depression and anxiety.

Thompson himself is maybe not the model for how to deal with disappointed hopes — the man’s writing severely dropped off in the late 70’s as his drug use became even more excessive, and his career more or less bumped along until his death by suicide in 20052.

But as an 18 year old, his attitude was particularly admirable to me: he looked his fears dead in the eyes, and then documented them for us as they ate him alive.

The antidote to fear

For a long time, I thought that fear was a fundamental element of my personality. Growing up, my family was obsessed with the pseudoscientific Enneagram personality typing system. The system, if you’ve never heard of it, is similar to Myers-Briggs (also considered pseudoscience by modern personality experts) in that it divides all people up into discrete personality types3.

The Enneagram was developed by Jesuits and Christian mystics who were attempting to explain human personalities in terms of which of the Seven Deadly Sins the person was more disposed to. They found this didn’t neatly describe all personality types, so they added two more sins (fear and deceit, though neither are canonical Deadly Sins) on for good measure, rounding us out to a neat 9 (Having 9 also allowed them to divide the types into three groups of three, and we all know the Catholics love a Trinity).

My type — the Six — was defined by the sin of fear, and so, for much of my early life, I believed this was an irrevocable part of my personality, something I would never be able to truly overcome. The so-called “virtue” of the Six type is “bravery.” But I never felt particularly brave, so I imagined myself as more or less screwed when it came to transcending my type. It is perhaps understandable that I became so smitten with Hunter S. Thompson, a man who embraced his fear (and also loathing, for good measure!).

For whatever reason, it took me a lot longer to dismantle my belief in the Enneagram than it did to dismantle my family’s conservative politics or Catholic faith, but once I did, I began to think of fear differently.

First: Fear is not a personality trait. Neither is anxiety. Fear is a natural response to real or perceived threats, and your body is correct to use it in certain situations. Anxiety is just fear directed at future events. Anxiety can be legitimate — something bad is coming and you can’t stop it — or speculative — something bad might happen and you can’t stop it — but it’s more likely to be a trauma response than just some innate part of who you are.

Second: I am convinced that the opposite of fear is not bravery. It’s curiosity. Frank Herbert’s Dune regularly employs the phrase “Fear is the mind-killer,” and if we believe that’s true, then what could we truly say awakens and animates the mind? Is it facing those fears head on? Or is it slipping to the side and trying to view the fear from a different angle?

The Benefits of Curiosity

One of the core components of anxiety is a sense of lacking control around the outcome of future events. I would argue that given our species current trajectory, anxiety is a rational thing to feel, because there are many ways in which our future feels outside of our control. When we try to take that future into our own hands, by say, putting pressure on our leaders, our leaders usually tell us it’s just not possible.

Given that it’s an age of disempowerment, it’s no surprise that it’s also an age of anxiety.

How exactly is one to be brave in this context? “Climate change may be raising the oceans and filling our skies with smoke, but I’ll face it head on!”

Great! Good luck breathing beneath the waves, or with a sky that’s on fire!

This isn’t to say that bravery is unimportant, it’s just to say that, in the process of facing our fears, it’s maybe 10 or 15 steps down the line. If you want to put your life back into your own control, first, you need knowledge, and to get knowledge, you need curiosity.

For example: It is not inherently brave to learn how to grow your own food. You just need to be willing to go out in your garden and, quite literally, muck around. You need to experiment with how certain plants grow and get a sense of what keeps them healthy and what kills them. People who get frustrated and give up when a plant dies never become gardeners, but people who are curious and are willing to learn from their mistakes will. And this is no small thing: if we wish to build more sustainable economies, we must begin to get as much of our food from close to home as possible. The point at which we must be brave — when we, say, start relying exclusively on ourselves and our neighbors for food — comes after years of learning.

Likewise, if we wish to build stronger, healthier, more equitable communities, the bulk of the work isn’t going to consist of iconically standing in front of a line of tanks. It’s going to be getting to know our neighbors and learning to work with them to build networks of support and care. To do this, you need to be curious: curious about their needs, curious about their histories, curious about how you can bring your different skills together to build something new.

It is a curious aspect of our society that we exalt the Brave, the people who run into burning buildings and save kittens. We give the Brave keys to the city. But it was not the Brave who developed flame retardant chemicals or insulated wiring: it was the Curious. The Curious undoubtedly saved infinitely more kittens in nearly every city on earth, but they will never get the keys to the city for the catastrophes they prevented, simply because we’ll never know what would’ve happened otherwise.

So by all means: If you can steel yourself to go out and slay the giant electric snake coming right at us in the sky, we’d all very much appreciate it. If you can’t, just study its habits.

Listeners to the audio version of this article get to hear my Hunter S. Thompson impression. I apologize to the late Doctor for my sins.

With one major resurgence, when, in 1994, he wrote a perfect eulogy for Richard Nixon that absolutely shit on the dead President’s grave: “the record will show that I kicked him repeatedly long before he went down. I beat him like a mad dog with mange every time I got a chance, and I am proud of it. He was scum.”

For those who are fans of these personality typing systems, don’t feel too bad — for a while, scientists believed personality was more static than it was, so these systems had some patina of legitimacy. We now know that personality exists instead on a series of spectrums, and that you move around on those spectrums through the course of your life. If you want to take a legit personality test, try out the Big Five. Note that legitimate systems don’t require you to pay a bunch of money to take their tests.

Also, to not shit completely on everyone’s parade, Myers-Briggs and the Enneagram do actually help a lot of people. This is because in spite of their pseudoscientific structures, they do drape those structures with a lot of legitimate science. The Enneagram in particular is popular among “exvangelicals,” people who have left behind fundamentalist churches. One could see how transitioning from one particularly toxic trinity to another that is actually packaged with decent advice and insight would be helpful, even if one hopes they eventually move past it.