What would an anarchist revolution look like?

In books like V for Vendetta, Infinite Detail, and The Dispossessed, anarchists present wildly different visions for how we'll make our way to a better future.

Yesterday, across England, Guy Fawkes was burned in effigy, 418 years after he tried to blow up parliament as part of the pro-Catholic Gunpowder Treason.

In the 21st century, Fawkes has come to represent something very different from what he did in his life: in his time, Fawkes wanted to restore a Catholic monarch to the throne of England, someone who would answer to the papacy in Rome. He could not have possibly wanted a more centralized government.

But in the 1980s, a comic book antihero named V donned Fawkes’ face as a mask, and thanks to the popularity of the comic, V for Vendetta — and its eventually movie adaptation — Fawkes switched in the collective unconscious from being a notorious papist terrorist to a symbol of the global anarchist movement.

While Fawkes, as the Guy who tried to blow up Parliament, is undoubtedly a cool symbolic figurehead, his actual historical status as a terrorist in the service of Catholic totalitarianism makes him a weird anarchist symbol. It also doesn’t help that the Fawkes mask has been used in a stunningly wide range of protests: against Scientology, against Middle East dictatorships, during Occupy, by the Anonymous hacktivist group, and by the morons who stormed the US Capitol on January 6th, to name a few.

As I’ve argued elsewhere, anarchist ideas deserve more attention from regular people, but are usually given short shrift in civics lessons. This isn’t that surprising: a movement that opposes authority is hardly going to be given a fair defense by the authorities themselves. I myself got a master’s degree from one of the world’s leading political science institutions, and still never once was given a clear definition of what anarchism was — I had to learn it for myself. (For a primer on basic anarchist ideas, watch the video below, or read this).

Anarchists are pretty good at expressing a vision of what the ideal society might look like. But how our current world gets from where it is to where the anarchists think we should be — that’s a lot trickier. The anarchist vision of utopia is so wildly different to the world we currently live in that it’s hard to imagine anything so alien ever coming into existence.

That does not mean, though, that authors haven’t tried. It’s worth taking a look at a few of them.

The violent overthrow: V for Vendetta

I love V for Vendetta1, but it is better as a work of fiction than as a work of anarchism. Writer Alan Moore was perhaps the world’s best comics writer at the time, and was doing a riff on superhero comics that also served as a criticism of Margaret Thatcher’s England in the 1980’s. The 80’s are when the UK really started stepping up its notorious mass surveillance, and Moore (accurately) saw the Thatcher government as a slide towards fascism.

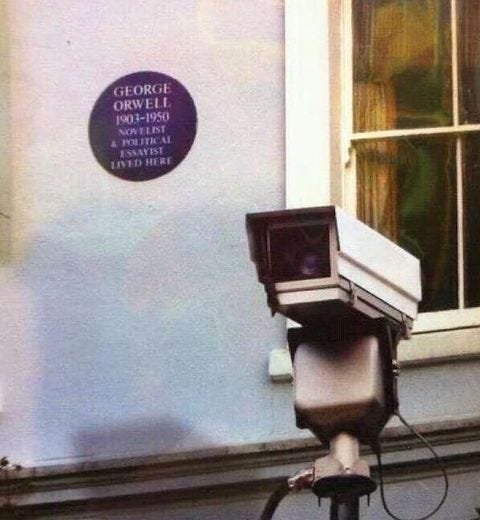

He pulled on dystopian works like Orwell’s 1984, imagined a slightly-futuristic fascist England, and then built his story around the imagery of Guy Fawkes blowing up Parliament. The comic has aged extremely well since then because since he and artist David Lloyd designed their totalitarian London, London itself has grown to look a lot more like what they designed. Moore has commented on the eeriness of living in a world he only once imagined, full of creeping authoritarian surveillance and full of people wearing his antihero’s haunting mask.

V for Vendetta is a lot less about anarchist theory than it is an indictment of fascism and people’s willingness to live in fear of their governments. On that count, it is great — but anarchists generally don’t believe it would be a good thing to have a single charismatic superhero overthrow the government.

Historically, anarchist movements within larger violent revolutions have been crushed. There are complicated reasons for this, but partly, it’s because revolutions have a tendency to cause power vacuums, and in the ensuing chaos, most of the groups involved are vying for power. A group that says “what if we gave the power to everyone?” tends to not win the day. With that said, anarchists have managed to set up small pockets of anarchist utopias in the midst of revolutionary chaos. Examples include:

The Paris Commune (crushed by French government)

Makhnovist Ukraine (crushed by Trotsky’s Red Army)

Revolutionary Barcelona (crushed by Stalinists)

Zapatista Autonomous Zones (still in existence)

Rojava (still in existence, but under attack by the governments of Syria and Turkey, as well as ISIS)

Regardless, the sheer size of modern nation states and their armies makes it difficult to imagine, say, an insurgent British or American anarchist force managing to get enough people to overthrow the government. So anarchists don’t usually spend a lot of time planning to go the V for Vendetta route.

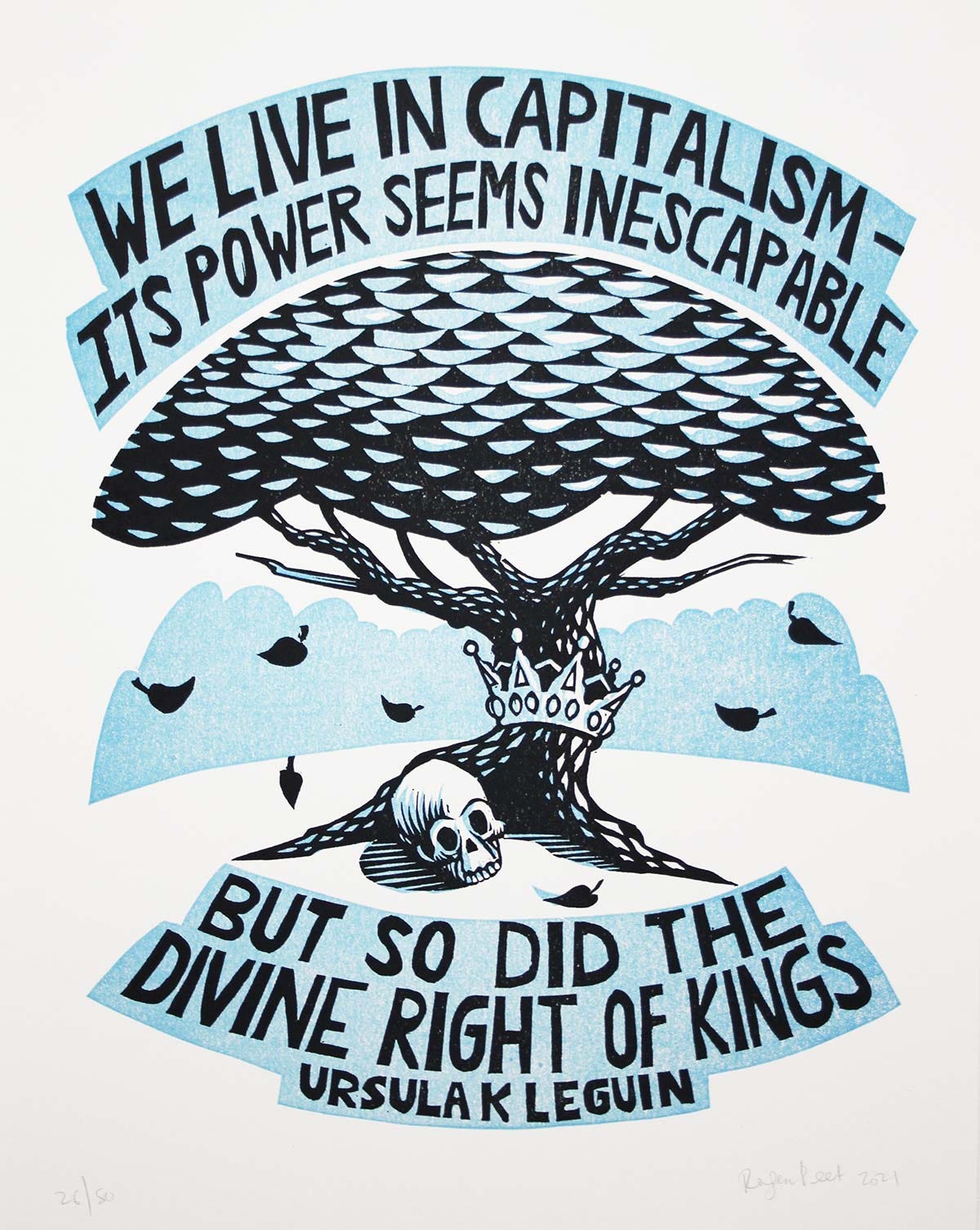

The flight: The Dispossessed

The most renowned anarchist utopia in fiction is Ursula K. LeGuin’s The Dispossessed. LeGuin neatly works around the need for a revolution by setting her story on a different planet. The planet — which resembles earth during the Cold War, with a liberal state and a competing authoritarian state fighting proxy wars in the smaller countries — has a moon, which the anarchists have been effectively exiled to, after their sect became too powerful on the home planet. In exchange for being granted their anarchist utopia, the anarchists are expected to give the two superpowers on the home planet shipments of the materials mined on the moon.

While this wouldn’t be argued as an ideal anarchist revolution by virtually anybody, as it turns out, it is how many egalitarian/anarchist societies have functioned historically. In James C. Scott’s book The Art of Not Being Governed, he talks about societies in upland Southeast Asia that managed, until the middle of the 20th century, to never fall under the power of a nation state.

These societies — derogatorily called “hill people” by the rulers of the valley kingdoms below — managed to survive by either fleeing from the state or by paying some form of tribute or making some sort of trade with them. By nature, Scott explains, these societies were egalitarian and were ever shifting — their ethnicities were blurred, because basically anyone who ran away from the states was welcome.

LeGuin uses her sci-fi device then, to recreate something that has in reality existed for millennia, not only in Southeast Asia, but in other difficult-to-reach areas of the world, where it was easy for people to flee from the long arm of the law2.

Pockets of freedom: Infinite Detail

For around 30 years, anarchists have spent a lot less time plotting overthrows of the government, and instead have focused on building autonomous zones. The concept was first explained by the controversial anarchist writer Hakim Bey3, who advocated for “Temporary Autonomous Zones” or areas where one could rapidly build a small-scale anarchist society and then dismantle it before the state could swoop in to repress it.

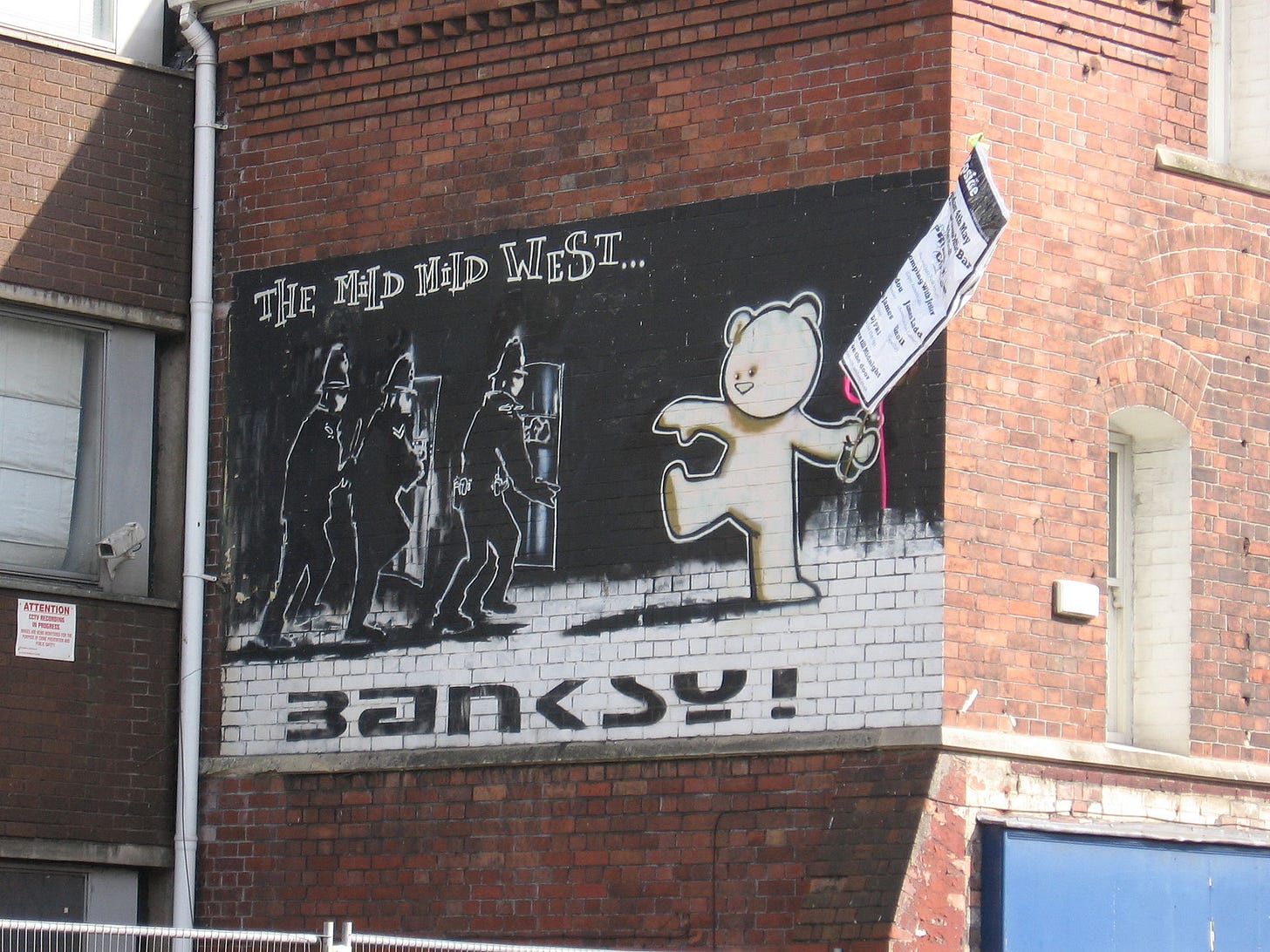

The most exciting form this idea took was in the Reclaim the Streets movement in Britain, where activists would swoop in and throw spontaneous street parties in public roads. The argument was that roads should be for people, not for cars, so during these parties, they’d be temporarily “liberating” streets for the public. They’d offer free food, games for kids, live music, even bouncy castles. When police showed up in riot gear, they would often quickly abandon the zone, only to construct another one later on.

In some places — particularly extremely left-wing neighborhoods or sections of a town, the autonomous zones have been able to become more permanent. In these places, certain laws may not be enforced, and certain practices may be accepted that are not allowed in other spots. Tim Maughan’s fantastic Infinite Detail imagines a sort of technological autonomous zone springing up in the left-leaning neighborhood of Stokes Croft in the city of Bristol in the UK.

The book follows the residents of the neighborhood (which they call “The People’s Republic of Stokes Croft”) as they try to build a sort of oasis where people are free from surveillance by the government and by corporations, and where the internet resembles less the modern algorithm-driven corporate hellscape it’s become, and more of the democratic, collaborative network its early advocates envisioned it as.

The book also follows the residents of Stokes Croft after a post-apocalyptic event where a group of hackers managed to crash the internet, taking the global economy down with it. UK society devolves into being ruled by street gangs, warlords, and quasi-governmental paramilitaries, while people who built the pre-crash Stokes Croft oasis work to sustain a vision of freedom that suddenly looks very different in the post-crash world.

Maughan is not, to my knowledge, an anarchist, and is mostly interested in problems around technology and the internet. But Infinite Detail is perhaps the best book I’ve read that explores whether, in our dystopian times, we can still try to build spaces and pockets where autonomy, freedom, and community are the core values, even as they’re surrounded by authoritarianism, greed, and the brutal realities of basic survival.

From my perspective, this is the only viable way in which the very good ideas that underly anarchism can begin to be put into practice — by enacting them right here and now, in the spaces underneath and in between the decaying structures of our modern society. Autonomy and self-rule are things that have to be practiced: if you overthrow a dictator, but the entire population is used to being ruled over, they’re likely to slip back into being ruled again. So at least as important as “how do we dismantle an unjust, exploitative system?” is the question “how do we learn to build something better underneath?”

On that journey, you could do worse than to start with V for Vendetta, The Dispossessed, and Infinite Detail.

Long time readers of this newsletter know that Alan Moore is literally my favorite writer in history, so any criticism of his work is given with a lot of love.

I live in New Jersey, and there’s actually a place here that the law has always had trouble maintaining control over: the Pine Barrens. Because of the dense forests and the terrible soil, the Pine Barrens remain a sparsely populated area in the middle of the largest urban sprawl on the eastern seaboard. Historically, the people who populate the Pine Barrens have been refugees from American society: Hessian deserters during the Revolutionary War, pirates who found in the creeks among the pines an ideal hideaway, runaway slaves, Native Americans who refused to relocate, and fugitives from the law. The people of the Barrens, or “Pineys” in local vernacular, are regularly slandered by “normal” New Jerseyans as backwoods inbred hicks. This prejudice led to the Pine Barrens being the place most targeted by early American eugenicists. But Piney pride remains in tact even in the 21st century — my friend

, a Piney, recalls being taught as a child the rhyme: “I am proud to be a Piney from my head down to my hiney.”Bey, also known as Peter Lamborn Wilson, is not well-liked in the anarchist movement because of his advocacy for pederasty. Anarchism’s core moral value is autonomy, even for children, which is why any suggestion that “pedophilia would be permissible” under an anarchist society is laughable, as pedophilia runs directly counter to the ideas of autonomy and consent. Regardless, Bey’s “Temporary Autonomous Zone” essay was influential, especially in Britain’s “Reclaim The Streets” movement and within the rave scene before people knew about his other positions. Even bad people can have good ideas sometimes.