Why mutual aid is one of the most important concepts to understand in the 21st century

How an early debate over Darwin's Theory of Evolution illuminates the political fights of our times

If there was one silver lining to the dumpster-fire pandemic year of 2020, it was the resurgence in the public eye of mutual aid. Mutual aid hadn’t gone anywhere, of course: it is something that the vast majority of humans engage in every day, and its proponents convincingly argue that it is older than the human race itself. Anyone who has lived through a catastrophe of some sort — a terrorist attack, a war, a wildfire, a tornado, an earthquake, a hurricane — is also familiar with the concept, even if they can’t put a name to it. This is because humans spontaneously reinvent mutual aid every time shit goes off the rails: the concept is encoded in our DNA.

What was special about 2020 was the scale of the catastrophe. There has not been a time in most people’s living memory when the disruption to everyday life was so abrupt and so ubiquitous. Suddenly, billions of people were in dire need of some form of help or assistance, and in all but the richest neighborhoods, the victims of the catastrophe were impossible to escape.

In America, COVID-19 strained the country’s already-abysmal social safety net to a breaking point. During the pandemic 60 million people turned to charities for food. Charities and government programs couldn’t help everyone, though, and into those gaps stepped mutual aid programs like community fridges and Food Not Bombs-style hot meal giveaways. While the government dragged its heels on suggesting masking to protect against the virus and redirected depleted stocks of PPE masks to hospitals, spontaneous communities of seamstresses and knitters produced thousands of homemade masks, which they gave to anyone in need1.

In much of the retrospective lore of COVID-19, the pandemic is depicted as an event that proved to many that humans can’t be trusted, focusing on the spread of misinformation, vaccine conspiracy theories, and needless public opposition to masks. The resurgence of mutual aid tells a quieter story, but if listened to carefully, it teaches the opposite: in moments of awfulness, humans are kind to one another, and we don’t have to rely on uncaring elites to take care of ourselves.

Let’s give a definition of mutual aid, and let’s refer to the great arbiter of modern knowledge, Wikipedia:

Mutual aid is an organizational model where voluntary, collaborative exchanges of resources and services for common benefit take place amongst community members to overcome social, economic, and political barriers to meeting common needs. This can include resources like food, clothing, to medicine and services like breakfast programs to education. These groups are often built for the daily needs of their communities, but mutual aid groups are also found throughout relief efforts, such as in natural disasters to pandemics like COVID-19.

For the next several weeks, Better Strangers will be focusing on the concept of mutual aid, particularly on how it’s a useful tool for those struggling with political despair, and how its core ethic provides a new path forward for a better future. Articles will include:

What mutual aid looks like in real life

“Disaster utopias,” and how they work

How COVID can be seen as a high point for humanity, not a low

An interview with the creator of a community fridge in Sacramento, and her struggle to keep the project afloat in a NIMBY neighborhood

Mutual aid in libraries

How non-profits are leaning into mutual aid in the 2020s

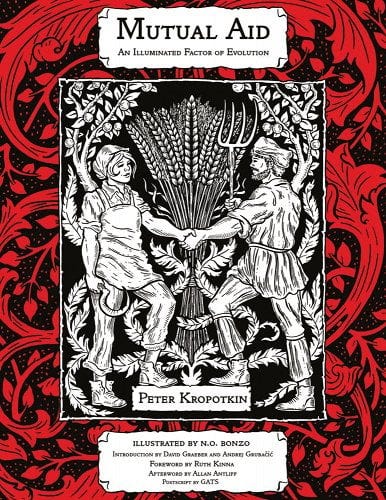

But for today, we’re going to discuss origins of the term, starting with the coiner of the phrase, Pyotr Kropotkin.

Pyotr Kropotkin and the battle against “Survival of the Fittest”

Within a couple decades of the publication of On the Origin of the Species, Charles Darwin’s ideas about biology and evolution were being coopted by regressive social movements to support racist and colonial policies. What Darwin had described as “natural selection2” was morphed into “survival of the fittest,” and this phrase was not just applied to biological systems, but to societies and races as well. Darwin’s ideas were revolutionary and exciting, and presented in the context of “survival of the fittest,” they seemed to offer a natural justification for some humans dominating others. Britain’s upper class were no longer brutal classists and racists, but were forward-thinking men of science, dedicated to the advancement of the species.

This strain of thought developed in all sorts of horrific directions — it offered justifications for colonialism, for racism, and for draconian attitudes towards the poor and destitute. It also led to the development of eugenics, which was fundamental to Nazi and American right-wing ideology in the early 20th century.

Some progressives — like the American William Jennings Bryan — used this right-wing tendency among Darwinists as a basis for arguing in favor of creationism3. But European radicals found their opposition in the far more coherent work of Pyotr Kropotkin.

Kropotkin had been born into an aristocratic family, but after his mother’s death at age three, he was raised by the servants and serfs of the household, giving him a lifelong preference for the underclass. In his 20’s, he was stationed in Siberia for a military posting. While there, he established himself as a talented geographer, and also became politically radicalized. This was in part because Siberia was where dissidents and free thinkers were sent into exile, but also because while mapping the Siberian terrain, Kropotkin regularly interacted with the local peasant farmers, whose decentralized and cooperative form of social organization he held in great esteem.

For extra income, Kropotkin translated the works of Herbert Spencer, the coiner of the term “survival of the fittest,” and he began to develop a counter-theory. He wrote, in the first paragraph of the resulting work:

Two aspects of animal life impressed me most during the journeys which I made in my youth in Eastern Siberia and Northern Manchuria. One of them was the extreme severity of the struggle for existence which most species of animals have to carry on against an inclement Nature; the enormous destruction of life which periodically results from natural agencies; and the consequent paucity of life over the vast territory which fell under my observation. And the other was, that even in those few spots where animal life teemed in abundance, I failed to find — although I was eagerly looking for it — that bitter struggle for the means of existence, among animals belonging to the same species, which was considered by most Darwinists (though not always by Darwin himself) as the dominant characteristic of struggle for life, and the main factor of evolution.

Instead, what he saw nearly everywhere was cooperation. He wrote a series of essays that were compiled into his seminal book Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution. His core argument wasn’t all that controversial: it was that while competition was indeed an important driver of evolution, cooperation within species was at least as important to that species survival.

This was a radical departure from how cooperation and altruism had been thought of by political theorists before him. The 18th century writer Jean-Jacques Rousseau had argued that what motivated altruism and cooperation was “universal love.” Kropotkin didn’t believe in anything so intangible. Cooperation persisted among species because it was practical, because it actively aided in a species survival. Indeed, in places like Siberia, where resources like food and shelter were scarce, cooperation seemed like a better way to survive than competition. This cooperation, or “mutual aid,”4 it seemed to him, was the main reason that species managed to thrive.

Kropotkin extended his argument further: in human societies, spontaneous mutual aid was the rule rather than the exception. He examined cultural studies of the indigenous peoples of the world and found countless examples of groups working together to survive and thrive. He tracked mutual aid through history, from the guilds of the medieval era to the (then contemporary) Paris Commune, and found that no matter how competitive and unjust our societies, human beings can’t seem to stop cooperating and working together for mutual benefit.

Kropotkin titled his work modestly: Mutual aid was A factor in evolution, not The factor. But the implications to the reader were obvious: humankind, indeed all animals, were not just competitive, they were cooperative, and much of the time, cooperation was the more effective means of survival than competition.

If Kropotkin was right — and in the 122 years since the publication of his book, it’s safe to say he was — then we do not need to accept right-wing arguments that competition, cruelty, and domination are what we must build our societies on. We could choose kindness and cooperation instead, and not just because that’s the morally right thing to do, but because it’s the smart and practical thing to do.

Coming next week

Next week’s article will be on what mutual aid looks like in the real world. I’ll go into some of the basic principles, how it looks different from charity and philanthropy, and through some examples of how people make mutual aid work in real life.

I hate doing this, but I’m going to paywall every other article in this series, because I want to be able to put a lot of time into these mini-courses, and I can’t justify doing that unless it’s making me money. The good news is that there are 7-day free trials enabled on my subscription page (linked below), and it’s only $5 a month. If you wanna be super cool, you can also donate a subscription to someone who can’t afford it. Everything I’m talking about, full disclosure, is also free on the internet — the Anarchist Library has a massive back catalogue of free radical texts, and you can find everything I’m talking about and more on that site.

My favorite mask from this era, a cute little blue guy with a bunch of goldfishes on it, was created by a coworker in one of these groups.

Darwin himself occasionally approved of the term “survival of the fittest” in some situations, but still in a biological context, not in a social or political one. He was an opponent of slavery, and did not believe that survival of the fittest should be the only rule in building good policy, but believed that interdependence and care for one another was important too. He also was — for his time — more open-minded than the average wealthy Englishman about the indigenous people of the Americas. But he was also sexist and not particularly progressive in his attitudes towards the poor.

Bryan famously argued this in the 1920 Scopes Monkey Trial.

The term mutual aid was not coined by Kropotkin, but by the Baltic zoologist Karl Kessler, who put forth the theory of mutual aid as the main factor of evolution in a 1879 lecture. Kroptkin was in attendance at this lecture, and further developed the theory when Kessler died before he could himself in 1881.

So stoked for this series on mutual aid! I love how well you're able to break down abstract or complicated ideas into actually clear and easy to understand descriptions🤘