Imagination and the search for a better future

If something has to be imagined before it can be built, what does it mean that all of the futures we're imagining are bleak?

This is part of the “Wondrous Creatures” series, which looks at the world through the philosophy and ideas of Alan Moore. Read more here.

A question for you: can you even imagine a better future for yourself and the planet? Take a moment and think about it. I am not controlling how fast you read this article.

Okay: what did you imagine? The overthrow of capitalism in a glorious revolution? Perhaps a kind of solarpunk ecotopia where we all grow our own food? A world where AI takes all the jobs we don’t want instead of all the jobs we do want? Where humans live in harmony with nature, a la the Navi in Avatar? A futuristic technotopia where we all surf around on hoverboards? A New York City where the skyscrapers are covered in edible native plants and you can dip a cup into the Hudson River and safely take a drink?

There’s no wrong answer here — the world you’d like to see is your own, and you are allowed to have a vision no one else has.

Rob Hopkins, the creator of the Transition Towns movement, regularly asks people to do this exercise at his speaking events. Transition Towns is a global movement trying to remake our communities into something more sustainable in the face of looming climate catastrophe. Hopkins started it in town of Totnes in Devon, England, and it quickly caught on and spread. There are now hundreds of Transition Network groups around the world.

In his truly excellent book From What Is to What If, Hopkins emphasizes what the single most important obstacle is to building our better future: lack of imagination. This is a major problem when it comes to climate change, because climate change is a problem that can only be solved with a staggering amount of imagination, and the problem is coming to a head at a moment when our collective imagination, it has to be said, has totally stagnated.

This isn’t necessarily an accident: we’ve got a stagnant collective imagination because we’re all so goddamn stressed we’re losing our goddamn minds. And this stress is the direct result of a wide swathe of policy decisions made by people in power: every time there’s a cut to social services, where food, healthcare, or other basic needs get a little more expensive, we get a little more stressed out. Every time we pick up our phones and go onto an app that has an algorithm designed to sap us of our attention so they can serve us endless ads, we get a little less focused, a little less free and playful in our minds. Our kids have it worse, because most of our schools aren’t designed to encourage playfulness and imagination, they are designed to encourage achievement and conformity.

See how quickly a discussion of our future can turn into a doom spiral? But there’s good news here: imagination is not a finite resource. If we could get ourselves into places where our thinking was freer, more playful, more imaginative, we could work ourselves out of all of these problems. For a look at how, we should take a look at some of the masters of imagination.

William Blake and the New Jerusalem

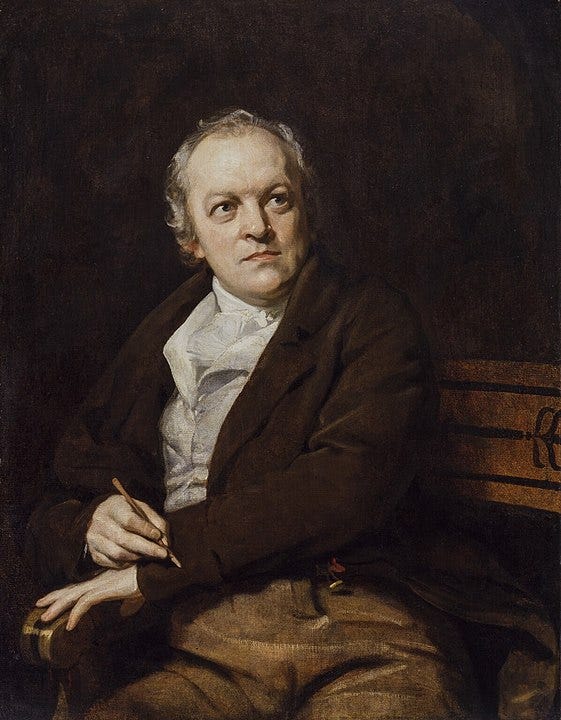

The patron saint of modern imagination has to be William Blake. Blake lived at the turn of the 18th and 19th centuries, producing extraordinary, visionary works of art and poetry during tumultuous times. Blake was regarded by many of his contemporaries as completely mad — he had a propensity for seeing heavenly visions even in adulthood, and his politics were what we would now recognize as anarchist. But his work today has come to define his native country, the United Kingdom, more than almost any other artist1.

One of his works, a poem titled And did those feet in ancient time, was put to music by Hubert Parry and retitled “Jerusalem.” It has now become the unofficial national anthem of the United Kingdom (behind “God Save the King”), where the poem paradoxically resonates with both the right and left on the political spectrum. It is a bizarre thing to find such common ground in such a radical poem, so I reproduce it in its entirety here:

“And did those feet in ancient time” by William Blake

And did those feet in ancient time, Walk upon Englands mountains green: And was the holy Lamb of God, On Englands pleasant pastures seen! And did the Countenance Divine, Shine forth upon our clouded hills? And was Jerusalem builded here, Among these dark Satanic Mills? Bring me my Bow of burning gold: Bring me my Arrows of desire: Bring me my Spear: O clouds unfold: Bring me my Chariot of fire! I will not cease from Mental Fight, Nor shall my Sword sleep in my hand: Till we have built Jerusalem, In Englands green & pleasant Land. "Would to God that all the Lords people were Prophets" Numbers XI. Ch 29

The poem serves as a sort of rallying cry for Blake’s overall philosophy, which is, to quote the Great Belinda Carlisle, that “heaven is a place on earth.” For Blake, heaven and hell were not otherworldly places, but real human experiences. Humans are capable of experiencing heaven — moments of joy, awe, and wonder — in their day-to-day life. They are also capable of experiencing moments of hell — despair, loss, agony — in their day-to-day.

Heaven, which Blake referred to as “Jerusalem” was something that could be built. He envisioned Jesus walking upon “Englands mountains green” way back in the past, and believes that if everyone worked together, they could build a new Jerusalem here in Britain where early capitalism — the famous “dark Satanic mills” — had already begun to take root.

The reason that it appeals to the right wing and the left is because the poem can be (mis)read as an ode to British exceptionalism. How the left reads it — and how Blake meant it, I believe — is as commitment to making the place he lived into something radically new, utopian, and heavenly.

The author

, in his excellent book William Blake vs. the World, suggests that what many people choose to see as madness in Blake could in fact be explained as an extraordinarily fertile imagination. This in itself isn’t unusual: Many children have what could be counted as visions, because their imaginations are so active and fertile and unbound by reason that they are able to literally see what they are imagining. This ability typically disappears as the higher reasoning faculties develop, but in Blake, the visions stayed for his entire life. Hence people thinking he was insane when he claimed to have seen a tree full of angels, or God’s face trying to push its way through the window.Blake seems to have understood that what he had was special, and that other people might benefit from it, and put an enormous amount of artistic effort into explaining and depicting his visionary worldview. For Blake, this was a utopian project, his gift to a world that might be better if “all the Lords people were Prophets.”

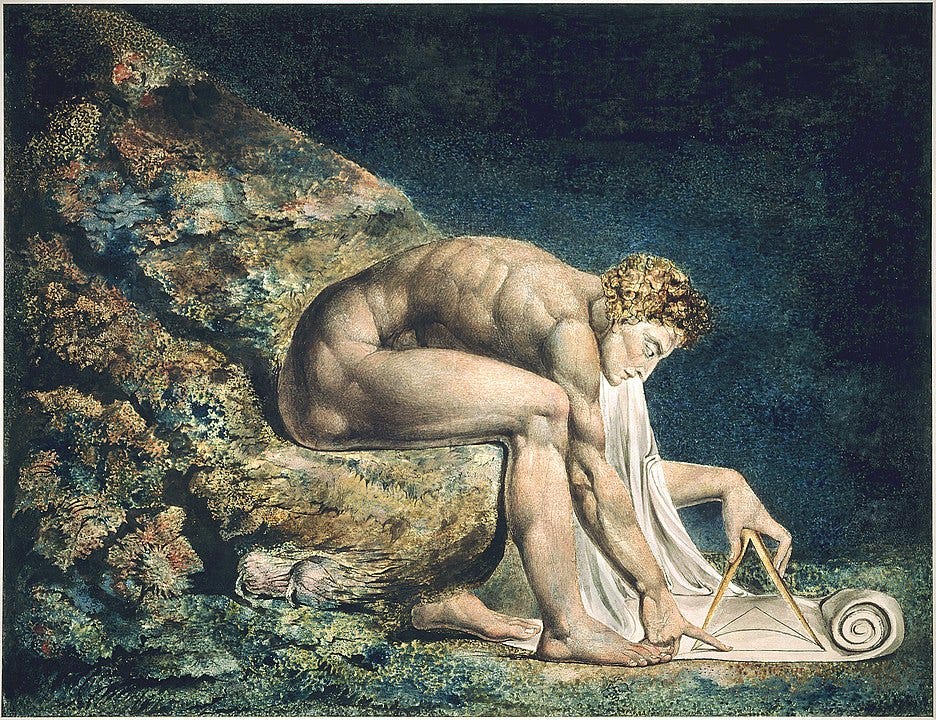

Higgs spends much of his book mapping the internal workings of Blake’s imagination. One thing Blake believed was that science and reason were important for understanding our world, but that if they were the only thing we focused on, we missed out on all of the other wonders of consciousness. His stand-in for the scientific materialist view of the world was the great scientist Sir Isaac Newton, who had died a quarter of a century before Blake’s birth, and loomed as one of the greatest Britons of all time. In Blake’s painting, Newton, he shows the scientist as fixated on his compass and scientific workings while sitting in a surreal, haunting landscape.

Higgs writes, “Newtons intense focus on the mathematical shapes he is drawing is intended as an attack on the Newtonian worldview — his narrow focus makes him unaware of the larger, organic, mysterious environment in which he works.”

In Blake’s worldview, reason was but just one tool available to us for understanding the world. We have to acknowledge that even our well-reasoned scientific theories have their roots in the murkier world of imagination. For Newton before Blake, this imaginative leap came with the famous falling of the apple, which led to his ideas about gravity. For Einstein after Blake, this jump came within a dream in which he imagined himself running alongside a light beam, which led to his discoveries around relativity.

As Blake puts it in his poem the “Proverbs of Hell”:

“What is now proved was once, only imagin’d.”

John Higgs on imagining a better future

Higgs, like Blake, is a writer fixated on the contours of the human imagination. His 2019 book, The Future Starts Here, is a work of experimental nonfiction focused on how our stunted imaginations are eroding our ability to actually build something better.

One symptom of this is the dystopian stories we’re absolutely awash in — somewhere in the past few decades, our culture became entirely fixated on dire warnings of apocalypse. Higgs writes:

It is sobering to think back over all the films you’ve seen in the past few decades, and try to find a vision of the future you’d want to live in. As far as I can tell, the last attempt at a utopian future in a mainstream Hollywood film was the 1989 comedy Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure. This was a future described as being fairly similar to now, but with better waterslides. By 1989, that was the best future our imagination could offer.

He juxtaposes this with the much-more-hopeful 1960s, the Golden Age of Sci-Fi, when one could write a hit show like Star Trek on the basis of the idea that, someday in the future, we’d figure our shit out, build an egalitarian society, and take our place among the other great civilizations of the universe out in the stars.

None of this is to say that dystopias don’t have their place: the truly great ones can help to highlight the dangers of going down certain political or economic paths, and can teach us something fundamental about our humanity. But one would hope that a balanced society would produce just as many utopias as it would dystopias. We need as many signposts pointing us in the right direction as we do signs warning us not to follow a certain path.

I talk about this quite a bit on TikTok, and whenever I do, someone tries to say that utopias are inherently boring, because in perfect worlds, there is no conflict. This, of course, is utter bullshit. Star Trek isn’t boring, and neither is Bill and Ted, for that matter. The false assumptions here are that:

A world that’s better than our own would be inherently “perfect,” and thus totally free of any conflict.

Writers, who are capable of creating vast universes out of nothing, aren’t capable of finding a good story in, say, a utopian solarpunk universe.

Becky Chambers’ solarpunk Monk and Robot duology, for example, is truly riveting writing where the core conflicts are that the main characters need a bit of a break from the grind sometimes. That we can’t imagine interesting stories in better worlds than our own is yet another failure of imagination.

The Four Weapons

Alan Moore has always maintained that the boundary between imagination and reality is porous, that we must imagine a chair before we can build a chair. The same must also be true of a brighter, better tomorrow. We can’t begin to build something that we can’t even imagine. Hopkins’ book encourages us to take a step further, by imagining this future with other members of our community, and starting in small ways.

Hopkins writes of Transition towns that decided collectively to pass ordinances that closed certain town roads to cars on certain evenings so kids could play in the street. This seemingly simple step had a huge knock-on effect: aside from the obvious benefits of getting kids away from their screens and out into the fresh air, they also found that by sending the kids into the streets, the parents also went into the streets, and many spoke to their neighbors for the first time. Out of this, a new sense of community was built, and out of this, more transition projects could be undertaken. Just by closing a few roads once a week in the evening.

As usual, Moore, as an experienced magician and artist, has advice for making the imaginary into the real. In his BBC Maestro Master Class (which is sadly paywalled)2 he suggests building your “Four Weapons,” which also happen to be the four suits of the Tarot Deck, which are connected both to the four elements and to specific human capacities. In ascending level of importance:

Coins (or Pentagrams) — Connected with the element of “Earth,” and the world of matter. To develop this weapon, you need to first pay attention to your material circumstances. You are going to have a hard time being imaginative and creative if you’re starving to death. But also, as a creative tool, you need to know how the world works. You need to understand how different actions have different consequences, and have some understanding of science and reality as it exists outside your body and in relation to it. In the writer sense, this means you probably shouldn’t write a book about the Peloponnesian War without having read a bit about it first. Likewise, if your aim is to rebuild the world, you probably need to have some understanding of why it’s broken in the first place3.

Swords — Connected with the element of “air,” and with the human intellect. Moore suggests that this is specifically the discriminatory intellect, the one that can tell the difference between a good idea and a bad idea. Because if you can’t tell the difference between the two, your own ideas are likely to be bad.

Cups — Connected with the element of “water” and with human emotion and compassion. In short, you have to have an understanding of why people are the way they are. If you don’t, you need to learn how to be able to put yourself into their shoes. This is especially important with bad people or characters. Whether you’re writing a story or trying to come up with political solutions, you need to understand why people — whom you might reasonably despise if you met them in public — might behave the way they do.

Wands — Connected with the element of “fire,” and with the human will. Moore classifies this as the most important weapon, as it is the one that motivates you to actually bring your ideas into the world rather than just keeping them in your head. This is the ability to get off your ass and actually do the thing, by marshalling the other three abilities and organizing them towards your goal.

While Moore’s understanding of bringing ideas into the world is centered around the writer/magician, it would serve equally as well for anyone trying to do anything creative, from reorganizing your fridge to building a better society. Subject your idea to four criteria:

Is it realistic?

Is it a good idea?

Is it a compassionate idea?

Do you (or your group) have the capacity to make it happen?

If your idea passes all four checks, there’s no reason you shouldn’t be able to make it reality.

Save possibly Shakespeare.

While the Maestro class is paywalled, much of this same information is offered up in Moore’s comic Promethea, which is a sort primer on his magical worldview.

Hint: It’s capitalism!